The English word wisdom originates from the Old English wīs (“wise”) and dōm (“judgment, decision, law”). The Proto-Germanic root wis- (“to see, to know”) connects wisdom to perception and insight. Related terms appear in Old High German (wīssag, “prophetic”), Old Norse (vísdómr), and Gothic (weisdumbs).

In Ancient Greece, wisdom was expressed as sophia, often referring to both practical skill and philosophical insight. The term was central to Greek philosophy, particularly in discussions on virtue.

The Latin equivalent, sapientia, derives from sapere (“to taste, to discern”), emphasizing wisdom as discerning between right and wrong.

Similar concepts exist in other languages:

Sanskrit: Jñāna and Viveka refer to intellectual and higher wisdom in Hindu thought.

Chinese: Zhì represents wisdom as practical intelligence, central to Confucian ethics.

Hebrew: Chokhmah in the Hebrew Bible is linked to divine and moral wisdom.

During the Hellenistic period, Alexander the Great’s campaigns brought about exchange of cultural ideas on its path throughout most of the known world of his era.

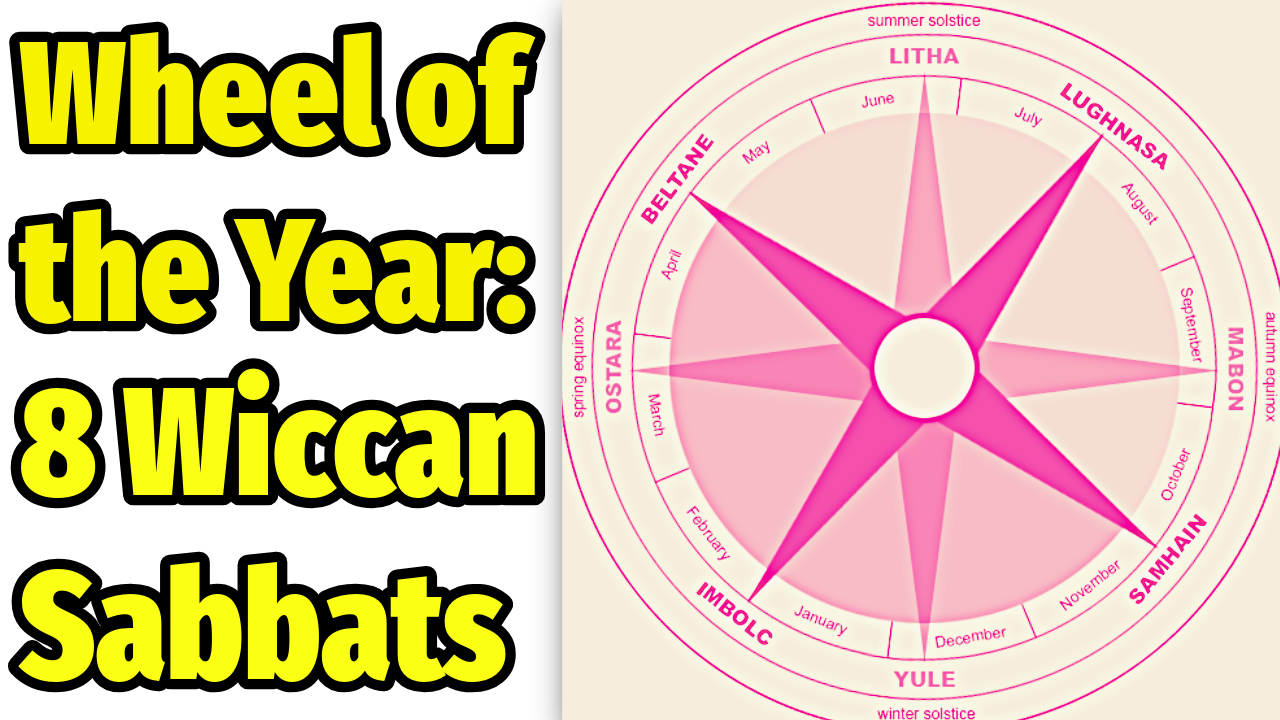

The Greek Eleusinian Mysteries and Dionysian Mysteries mixed with the Cult of Isis, Mithraism and Hinduism, along with some Persian influences.

The perennial wisdom or perennial philosophy originates from a blend of Neo-Platonism and Mediterranean syncretic cultures.

Neo-Platonism was founded by Plotinus and influenced by Plato.

At the most fundamental level, Plato says abstract objects exist in a “third realm” distinct from both the sensible external world and the internal world of consciousness.

Plotinus was also influenced by the teachings of classical Greek, Persian, and Indian philosophy and Egyptian theology.

His metaphysical writings later inspired numerous Pagan, Jewish, Christian, Gnostic and Islamic metaphysicians and mystics over the centuries.

Plotinus taught that there is a supreme, totally transcendent “One”, containing no division, multiplicity, nor distinction; likewise, it is beyond all categories of being and non-being.

The One “cannot be any existing thing” and cannot be merely the sum of all such things but “is prior to all existing things”.

Perennialism has its roots in the Renaissance-era interest in Neo-Platonism and its idea of the One from which all existence emerges.

It was an influential philosophy throughout the Middle Ages and its ideas were integrated into the philosophical and theological works of many of the most important medieval thinkers.

It is a philosophical and mystical perspective that suggests a core, timeless wisdom existing across various religions and cultures, revealing universal truths about the nature of reality, humanity, and consciousness. This wisdom is believed to be present in different forms and languages across different traditions.

There is no universally agreed upon definition of the term “perennial philosophy”, and various researchers have employed the term in different ways.

For all perennialists, the term denotes a common wisdom at the heart of world knowledge, but exponents across time and place have differed on whether, or how, it can be defined.

Some perennialists emphasize a sense of participation in an ineffable truth discovered in mystical experience, though ultimately beyond the scope of complete human understanding.

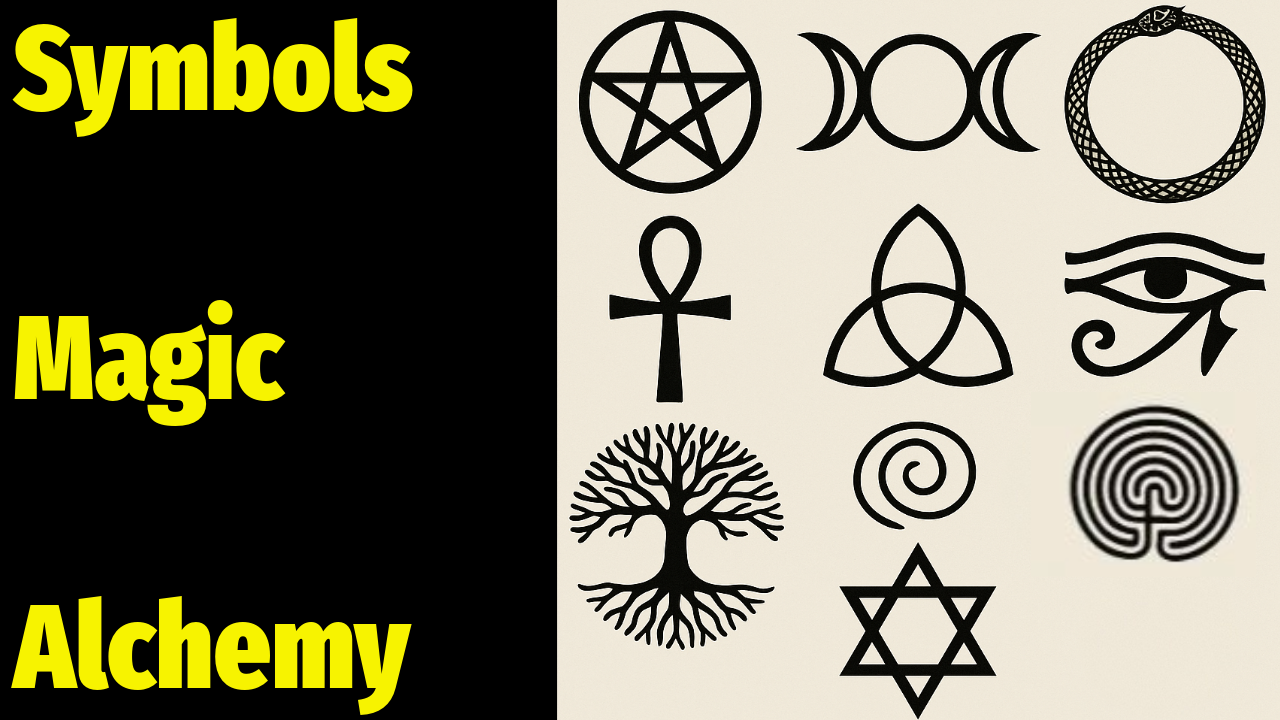

Others argue that Occult Teachings share a single metaphysical truth and origin from which all esoteric and exoteric knowledge and doctrine have developed.

According to this theory, the original Being initially emanates the nous, which is a perfect image of the One and the archetype of all existing things. It is simultaneously both being and thought, idea and ideal world.

What Plotinus understands by the nous is the highest sphere accessible to the human mind, while also being pure intellect itself.

The Demiurge (the nous) is the energy, or ergon (it does the work), which manifests and organizes the material world into something perceivable.

Later Neoplatonic philosophers added hundreds of intermediate beings such as Gods, angels, demons, and other entities as mediators between the One and humanity.

The Neoplatonist Gods are omni-perfect beings and do not display the usual behavior associated with their representations in the myths.

The One: God, The Good. Transcendent and ineffable.

The Hypercosmic Gods: those that make Essence, Life, and Soul

The Demiurge: the Creator

The Cosmic Gods: those who make Beings, Nature, and Matter.

Evil

Neoplatonists did not believe in an independent existence of evil. They compared it to darkness, which does not exist in itself but only as the absence of light.

Evil is simply the absence of good. Things are good as long as they exist and they are evil only when they are imperfect, lacking some good, which they should have.

Neoplatonists believed human perfection and happiness were attainable in this world, without awaiting an afterlife.

Perfection and happiness, seen as synonymous, could be achieved through philosophical contemplation.

The neoplatonists believed in the pre-existence and immortality of the soul.

All people return to the One, from which they emanated.

Roman world: Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (25 BCE–50 CE) attempted to reconcile Greek Rationalism with the Torah.

Philo translated Judaism into terms of Stoic, Platonic and Neopythagorean elements, and held that God is “supra rational” and can be reached only through “ecstasy”. He also held that the oracles of God supply the material of moral and religious knowledge.

Renaissance

Agostino Steuco (1498–1548) was an Italian humanist, Old Testament scholar and antiquarian. He discoursed on the subject of wisdom and perennial philosophy and coined the term philosophia perennis.

According to him, there is “one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples.”

This single knowledge (sapientia) is the key element in his philosophy, emphasizing continuity over progress. Steuco’s idea of philosophy is not one conventionally associated with the Renaissance.

Indeed, he believed that truth is lost over time and is only preserved in the prisca theologia.

He held that philosophy works in harmony with religion and should lead to knowledge of God, and that truth flows from a single source, more ancient than the Greeks.

Steuco was strongly influenced by Iamblichus’s statement that knowledge of God is innate in all, and also gave great importance to Hermes Trismegistus.

Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) believed that Hermes Trismegistus, the supposed author of the Corpus Hermeticum, was a contemporary of Moses and the teacher of Pythagoras, and the source of both Greek and Christian thought.

He sought to integrate Hermeticism with Greek and Christian thought, discerning a prisca theologia found in all ages.

The Prisca Theologia, “venerable and ancient theology”, which embodied the truth and could be found in all ages, was a vitally important idea for Ficino.

He argued that there is an underlying unity to the world, the soul or love, which has a counterpart in the realm of ideas.

Ficino was influenced by a variety of philosophers and mystical writings and saw his thought as part of a long development in philosophical truth.

Prisca theologia is related to concept of perennial philosophy, but an essential difference is that prisca theologia is understood to have existed in pure form only in ancient times and has since undergone continuous decline and dilution but perennial philosophy asserts that the “true religion” periodically manifests itself in different times, places, and forms, potentially even in modern times.

Both concepts, however, do suppose a unique true religion and tend to agree on its basic characteristics.

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), a student of Ficino, went further than his teacher by suggesting that truth could be found in many traditions, rather than just in the Bible or Aristotelian teachings.

He proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle and saw aspects of the Prisca Theologia in Averroes, the Quran, Kabbalah, and other sources. According to him, truth could be found in many traditions.

He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, natural philosophy, and magic against all comers, for which he wrote the Oration on the Dignity of Man, which has been called the “Manifesto of the Renaissance”.

In the Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem (Treatise Against Predictive Astrology) he critiques predictive astrology.

It was written in 1493 but not published until after Pico’s death in 1496. The treatise argues that astrology lacks philosophical and scientific grounding and is riddled with inconsistencies.

Evidence for perennial philosophy

Cognitive archeology such as analysis of cave paintings and pre-historic art and customs suggests that a form of perennial philosophy or Shamanic metaphysics was present in many ancient cultures all around the world. Similar beliefs are still found in many present-day cultures.

Perennial philosophy postulates the existence of a parallel or concept world alongside the day-to-day world, and interactions are possible between these worlds during dreaming and ritual, or on special days or at special places.

As we proposed in previous videos, this Syncretic perspective can be linked to Occult and Esoteric Pragmatism, the practical use of mystical and hidden knowledge in daily life.

What do you think of Perennial Wisdom and its concepts? Are you a Syncretist? Do you believe in the Immortality of the Soul? What do you think of Occult and Esoteric Pragmatism? Let us know in the comment section, subscribe and share the POST!!!

Check our website for consultations, tarot readings, exclusive videos, courses, occult related items and more!!!

Video version with images here:

Perennial Wisdom – Occult Knowledge – Syncretism – Esoteric Pragmatism

Interesting sources, additional info, courses, images, credits, attributions and other points of views here:

Balancing and Healing the Chakras through Yoga https://www.udemy.com/course/balancing-and-healing-the-chakras-through-yoga/?referralCode=12C81A148616B419AA06

Mudras to Balance and Harmonize your Chakras and Energy Body https://www.udemy.com/course/mudras-to-balance-and-harmonize-your-energy-body/?referralCode=1A275C6E67E05E8C8130

Elemental Energy for Success and Well Being https://www.udemy.com/course/elemental-energy-for-success-and-well-being/?referralCode=A680413E03BEAD96E744

Book a Tarot reading here: https://www.suryaholistictarot.com/book-a-reading/

Check our soundtracks here:

https://lennyblandino.bandcamp.com/track/nivuru-synthetic-waves

Websites:

https://www.staciebronson.com/

Links and References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perennial_philosophy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prisca_theologia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marsilio_Ficino

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Pico_della_Mirandola

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neoplatonism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syncretism

https://www.nodualidad.info/maestros/agostino-steuco.html

Pics:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marsilio_Ficino#/media/File:Corpus_Hermeticum.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plotinus#/media/File:Plotinos.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platonism#/media/File:Head_Platon_Glyptothek_Munich_548.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DIKW_Pyramid.svg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Filippo_Gherardi_-_The_Triumph_of_Wisdom_-_WGA08669.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_religions#/media/File:Religious_syms_bw.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysticism#/media/File:Mevlana_Konya.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysticism#/media/File:Hildegard_von_Bingen_Liber_Divinorum_Operum.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysticism#/media/File:Flower_of_Life_19-circles.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysticism#/media/File:Josep_Benlliure_Gil43.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysticism#/media/File:Abulafia.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syncretism#/media/File:Jesuits_at_Akbar’s_court.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenistic_period#/media/File:Gandhara_Buddha_(tnm).jpeg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plato#/media/File:Plato_Silanion_Musei_Capitolini_MC1377.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philo#/media/File:PhiloThevet.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Pico_della_Mirandola#/media/File:Pico1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamanism#/media/File:Witsen’s_Shaman.JPG

https://pixabay.com/illustrations/background-astrology-beige-calendar-1874722

https://pixabay.com/photos/books-shelves-door-entrance-1655783

https://pixabay.com/photos/saint-priest-faith-holy-man-old-2356564

https://pixabay.com/photos/helianthus-flower-yellow-flower-8408797

https://pixabay.com/photos/old-man-beard-portrait-face-hand-5564731

https://pixabay.com/photos/read-religion-man-sit-faithful-1795153

https://pixabay.com/photos/woman-anne-married-mother-girl-7672264

https://pixabay.com/photos/tara-female-peaceful-manifestation-163076

https://pixabay.com/photos/statue-read-sun-red-wisdom-3798990

https://pixabay.com/photos/egypt-sphinx-pyramid-cairo-giza-2133951

https://pixabay.com/illustrations/angel-devil-demon-monster-horror-8152917

https://pixabay.com/illustrations/sunset-boy-open-arms-gesture-110305