The Kingdom of Kush, also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

The native name of the Kingdom was recorded in Egyptian as kꜣš.

The name Kush has been connected with Cush in the Hebrew Bible. According to the Bible, Nimrod, a son of Cush, was the founder and King of Babylon.

In Greek sources Kush was known as Kous or Aethiopia.

The region of Nubia was an early cradle of civilization, producing several complex societies that engaged in trade and industry. The city-state of Kerma emerged as the dominant political force between 2450 and 1450 BC, controlling an area in the Nile Valley as large as Egypt.

The Egyptians were the first to identify Kerma as “Kush” probably from the indigenous word “Kasu”. Over the next several centuries the two civilizations engaged in intermittent warfare, trade, and cultural exchange.

In the Kingdom of Kerma’s latest phase, lasting from about 1700 to 1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Saï and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt. Current Sai Island is located in northern Sudan.

Under Thutmose I, Egypt made several campaigns south, occupied Kush and destroyed its capital, Kerma.

Egyptians also undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under the rule of Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC). The Kushites are described as archers:

“Now after his Majesty had slain the Bedoin of Asia, he sailed upstream to Upper Nubia to destroy the Nubian bowmen.”

Archers were the most important force in the Kushite military. Their arrows were often poisoned-tipped. Elephants were occasionally used in warfare, as seen in the war against Rome around 20 BC.

Around 1500 BC, Nubia was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. After the conquest, Kerma culture was increasingly Egyptianized. Nubia nevertheless became a key province of the New Kingdom, economically, politically, and esoterically. Major pharaonic ceremonies were held at Jebel Barkal near Napata.

According to Josephus Flavius, the biblical Moses led the Egyptian army in a siege of the Kushite city of Meroe. To end the siege, Princess Tharbis was given to Moses as a “diplomatic” bride, and thus the Egyptian army retreated back to Egypt.

With the disintegration of the New Kingdom around 1070 BC, Kush became an independent kingdom centered at Napata in modern northern Sudan. This more-Egyptianized “Kingdom of Kush” emerged and regained the region’s independence from Egypt.

The extent of cultural and political continuity between the Kerma culture and the chronologically succeeding Kingdom of Kush is difficult to determine.

The first Kushite King known by name was Alara, who ruled somewhere between 800 and 760 BC.

Alara was a King of Kush, who is generally regarded as the founder of the Napatan royal dynasty and was the first recorded prince of Kush. He never controlled any region of Egypt during his reign compared to his two immediate successors. Nubian literature credits him with a substantial reign since future Nubian kings hoped that they might enjoy a reign as long as Alara’s.

His memory was also central to the origin myth of the Kushite Kingdom, which was embellished with new elements over time. Alara was a deeply revered figure in Nubian culture and the first Kushite King whose name came down to scholars.

Later royal inscriptions remember Alara as the founder of the dynasty, some calling him “chieftain”, others “king”.

Alara was probably buried at El-Kurru, although there exists no inscription to identify his tomb. It has been proposed that it was Alara who turned Kush from a chiefdom to an Egyptianized kingdom centered around the cult of Amun.

Alara’s successor Kashta extended Kushite control north to Elephantine (near modern-day Aswan) and Thebes in Upper Egypt.

Kashta’s successor Piye seized control of Lower Egypt around 727 BC.

He ruled from the city of Napata, located deep in Nubia, modern-day Sudan.

“Amun of Napata granted me to be ruler of every foreign country,” and Amun of Thebes granted me to be ruler of the Black Land (Kmt)”.

“Foreign country” in this regard seems to include Lower Egypt, while “Kmt” seems to refer to a united Upper Egypt and Nubia.

KMT is probably the root of the word Kemet, where Al-Kimia (Alchemy) derives from.

The monarchs of Kush ruled Egypt for over a century until they were expelled by the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in the mid-seventh century BC.

King Esarhaddon, when conquering Egypt and destroying the Kushite Empire, stated how he “deported all Aethiopians from Egypt, leaving not one to pay homage to me”.

He was talking about the Nubian 25th Dynasty rather than people from modern-day Ethiopia.

The 25th dynasty was a line of pharaohs who originated in the Kingdom of Kush.

Most of this dynasty’s kings saw Napata as their spiritual homeland. They reigned in part or all of Ancient Egypt for nearly a century, from 744 to 656 BC.

The 25th dynasty was highly Egyptianized, using the Egyptian language and writing system as their medium of record and exhibiting an unusual devotion to Egypt’s religious, artistic, and literary traditions.

Earlier scholars have ascribed the origins of the dynasty to immigrants from Egypt, particularly the Egyptian Amun priests.

Tantamani was the last pharaoh of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty. His royal name was Bakare, which means “Glorious is the Soul of Re.”

Soon after the Assyrians had appointed a king and left, Tantamani invaded Egypt in hopes of restoring his family to the throne. Tantamani marched down the Nile from Nubia and reoccupied all of Egypt, including Memphis. The Assyrians’ representatives were killed in Tantamani’s campaign.

This led to a renewed conflict with Ashurbanipal in 663 BCE. The Assyrians returned to Egypt in force and defeated Tantamani.

This event effectively ended Nubian control over Egypt, although Tantamani’s authority was still recognised in Upper Egypt until 656 BCE, when Egypt was unified. These events marked the start of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

Thereafter, Tantamani ruled only Nubia (Kush). He died in 653 BCE and was buried in the family cemetery at El-Kurru, below a pyramid, now disappeared. Only the entrance and the chambers remain, which are beautifully decorated with mural paintings.

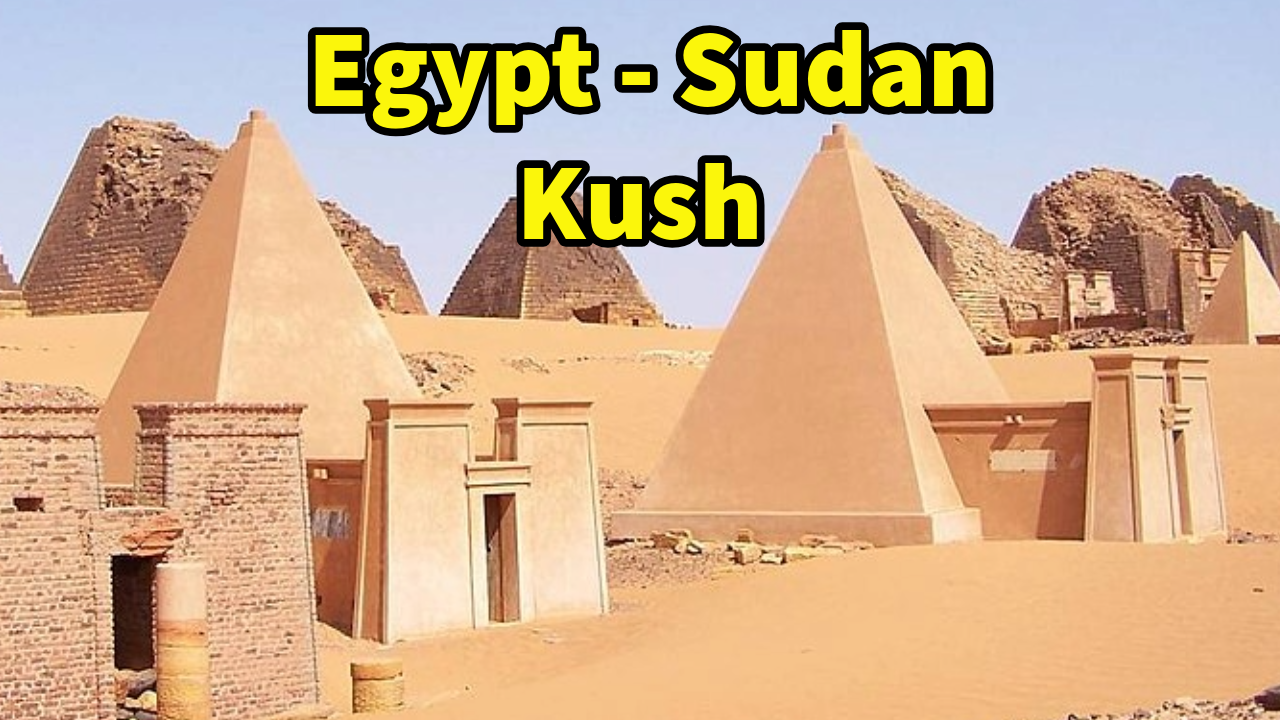

The Kushite pharaohs built and restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal. It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile Valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern-day Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.

King Aspelta moved the capital to Meroë, considerably farther south than Napata, circa 591 BCE, because it was on the fringe of the summer rainfall belt, and the area was rich in iron ore and hardwood for iron working. The location also afforded access to trade routes to the Red Sea. The Kushites traded iron products with the Romans, in addition to gold, ivory and slaves.

Around 300 BCE, the move to Meroë was made more complete when the Kings began to be buried there, instead of at Napata. One theory says that the monarchs wanted to break away from the power of the priests at Napata.

During this same period, the Kushite authority may have extended some 1,500 kms along the Nile River valley from the Egyptian frontier in the north to areas far south of modern-day Khartoum and probably also substantial territories to the east and west.

The fall of Meroe is often associated with an Aksumite invasion, although Aksum’s presence in Nubia was likely short-lived.

The Kingdom of Aksum was based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. It was considered one of the 4 great powers by the Persian prophet Mani, alongside Persia, Rome, and China.

From the third century BCE to the third century AD, northern Nubia would be invaded and annexed by Egypt. Ruled by the Macedonians and Romans for the next 600 years, this territory would be known in the Greco-Roman world as Dodekaschoinos.

After the Romans assumed control of Egypt, they negotiated with the Kushites at Philae and drew the southern border of Roman Egypt at Aswan.

The Kingdom of Kush became a client kingdom of Rome, which was similar to the situation under Ptolemaic rule of Egypt. Kushite ambition and excessive Roman taxation are two theories for a revolt that was supported by Kushite armies.

The ancient historians Strabo and Pliny give accounts of the conflict with Roman Egypt in the first century BCE. According to Strabo, the Kushites sacked Aswan with an army of 30,000 men and destroyed imperial statues.

Then, the Kushites sent ambassadors to negotiate a truce with the Romans, obtaining a peace treaty on favorable terms. Trade between the two nations increased and the Roman Egyptian border was moved to Maharraqa.

This arrangement guaranteed peace for most of the next 300 years and there is no definite evidence of further clashes.

Kush began to fade as a power by the first or second century AD, drained by the war with the Roman province of Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.

It has been suggested that the Kushites reoccupied lower Nubia after Roman forces were withdrawn to Aswan. Thereafter, it weakened and disintegrated due to internal rebellion.

The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a major regional power until the 4th century AD when it weakened from internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions and invasions and conquest of the Kingdom of Kush by the Noba people who introduced the Nubian languages and gave their name to Nubia itself.

Around 420 AD, the elites began assuming royal insignia of their own, resulting in the later kingdoms of Nobatia (north), Makuria (center), and Alodia (south). Out of these 3, Nobatia is considered a small post-imperial remnant of Kush, maintaining some aspects of Kushite culture but also exhibiting Hellenistic and Roman influences.

Sometime after this event, the Kingdom of Alodia would gain control of the southern territory of the former Meroitic empire including parts of Eritrea.

Technology, medicine, mathematics and architecture

The natives of the Kingdom of Kush developed a type of water wheel that had a decisive influence on agriculture.

They also developed a form of reservoir, known as hafir.

The functions of hafirs were to catch water during the rainy season for storage, to ensure it was available for several months during the dry season as drinking water, to irrigate fields and for cattle.

Nubian mummies revealed that Kush was a pioneer of early antibiotics. Tetracycline was already being used by Nubians, while modern commercial use started in the mid 20th century.

The theory states that earthen jars containing grain used for making beer contained the bacterium streptomyces, which produced tetracycline, and Nubians could have noticed that people felt better by drinking beer.

Nubians had a sophisticated understanding of mathematics as they appreciated the harmonic ratio and established a system of geometry to create early versions of sun clocks.

Long overshadowed by its more prominent Egyptian neighbor, Kush was an advanced civilization in its own right. The Kushites had their own unique language and script, maintained a complex economy based on trade and industry, mastered archery and developed a complex, urban society with uniquely high levels of female participation.

Though Kush had developed many cultural affinities with Egypt, such as the veneration of Amun, and the royal families of both kingdoms occasionally intermarried, Kushite culture, language and ethnicity was distinct, even the way they dressed, their appearance and method of transportation.

They also created pyramids, mud-brick temples (deffufa), and masonry temples.

Pyramids are “the archetypal tomb monument of the Kushite royal family” and found at “el Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroe.”

The Kushite pyramids are smaller with steeper sides than northern Egyptian ones.

Kush also invented Nubian vaults, a type of curved surface forming a structure of pure earth without the need of timber.

Some scholars believe the economy in the Kingdom of Kush was a redistributive system. The state would collect taxes in the form of surplus produce and would redistribute it to the people. Others believe that most of the society worked on the land and required nothing from the state and did not contribute to the state.

Northern Kush seems to have been more productive and wealthier than the Southern area.

On account of the Kingdom of Kush’s proximity to Ancient Egypt and because the 25th dynasty ruled over both states in the 8th century BCE, the political structure and organization of Kush as an independent ancient state has not received as thorough as attention from scholars, and there remains much ambiguity especially surrounding the earliest periods of the state.

The study of the region could benefit from increased recognition of Kush as an entity in its own right, with distinct cultural conditions, rather than merely as a secondary reign on the periphery of Egypt.

What do you think about the Kingdom of Kush and its history? Let us know in the comment section and share the post!!!

Video version here:

The Kushite Empire (Kingdom of Kush) Sudan – Egypt

Interesting sources, additional info, images, credits, attributions and other points of views here:

Elemental Energy and how to use it, check our course here: https://www.udemy.com/course/elemental-energy-for-success-and-well-being/?referralCode=A680413E03BEAD96E744

Book a Tarot reading here: https://suryaholistictarot.com/book-a-reading/

Check our soundtrack here:

https://lennyblandino.bandcamp.com/track/fire-meditation-1

Websites:

https://www.staciebronson.com/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1372429986896515

LINKS:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Kush

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aethiopia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esarhaddon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-fifth_Dynasty_of_Egypt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sa%C3%AF_(island)

https://medievalsaiproject.wordpress.com/

https://lenditravel.com/destinations/sai-island/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El-Kurru

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alara_of_Kush

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jebel_Barkal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubian_vault

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tantamani

PICS:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kushite_heartland_and_Kushite_Empire_of_the_25th_dynasty_circa_700_BCE.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wallpaper_group-pmg-4.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Relief_In_The_Semna_Temple_(3)_(34074139275).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gebel_Barkal.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lepsius_el-Kurru_pyramids.jpeg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rulers_of_Kush,_Kerma_Museum.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pyramids_of_Nuri_(cropped).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Tanutamani,_el-Kurru.jpeg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tetracycline-HCl_substance_photo.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sudan_Meroe_Pyramids_30sep2005_2.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_Amon_Napata_elevation_2.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Naqa_Apedamak_temple.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taharqa_%26_Shabaka_papyrus,_Thebes.jpeg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taharqa%27s_kiosk._Karnak_Temple.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pharaoh_Taharqa_of_Ancient_Egypt%27s_25th_Dynasty.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Outline_of_Nubia.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tanotamun_portrait_in_Kerma_Museum.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christian_Nubia.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Al-Kurru,main_pyramid.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JebelBarkalMutTemple3.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Napata_english2.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cartouche_Alara_Lepsius.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jebel_Barkal.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colossal_statue_of_King_Aspelta_MFA.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aksumite_Empire,_according_to_Momentum_Adulitrum.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient-egyptian-sundial.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egypt_-_Capture_of_Memphis_by_the_Assyrians.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubia#/media/File:Nubia_NASA-WW_places_german.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubia#/media/File:Nubian_Archers.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Egypt#/media/File:NE_565ad.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triakontaschoinos#/media/File:Nubia_today.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubian_vault#/media/File:Voute_nubienne_egypte.jpg